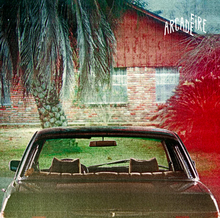

Album name: The Suburbs

Album name: The Suburbs

Artist name: Arcade Fire

Genre: Indie Rock

Released: August 2, 2010

Label: Merge/Mercury

ZME Rating: 9/10

Website: arcadefire.com

A tremendous amount of hype has surrounded Arcade Fire since they released their self-titled EP back in 2004. By fusing bits of the Polyphonic Spree and Talking Heads and interweaving the more jaunty songs from Pavement’s back collection, Arcade Fire has been able to create a rather interesting, albeit exciting sound that jumps from offhandedly shuffled ballads to jangling anthems. They have made a name for themselves with their now classic debut, Funeral, and performance at the Grammy’s with David Bowie. Now, in 2010, they are back and have released an album that BBC says is possibly better than Radiohead’s classic opus OK Computer.

Arcade Fire is no stranger to, nor do they shy away from themes like death, pyramid schemes, and rebellion, but this time around they are focusing their energies into something more sinister – growing up. The Suburbs is generally about everything the name states: shedding childish naivety, social isolation among peers, learning to drive, etc. The remarkable thing about this album is how tender and minimal it is. Despite its 16 song length (spanning a little over 60 minutes) this album is far more grounded and personal than its predecessors; although, there is a sense of continuity here. Maybe their albums are asort of storyline, one that grows with you as you grow with the band. Funeral, focused on the laws and boundaries that adults enforced and the mere naive inquiry of a child (think The Giver); while 2008’s Neon Bible was a testament of media and corporate schemes overtaking society (those children growing into adults and dealing with the problems that made their parents come home stressed, tired and without a childish sense of imagination). I guess that would make the Suburbs and adult’s nostalgic look into their childhood, a time when their only problems were who they were dating and which band is better Nirvana vs Pearl Jam. That may sound a bit condescending, but there are other themes as well, and those are the themes that anchors this album evoking empathetic pain. They sing about things like an artist’s battle against the small-mindedness of pretentious hipsters, trying to create art when the masses and businessmen only want simplicity and accessibility.

Now to the music, opening song starts rather abruptly with a cymbal crash and reserved piano line. After the initial shock, you are quickly soothed into its dream-like atmosphere, it’ll like you’ve always been there really. The title track with its jaunty piano and slightly danceable shuffle talks about the monotony of the suburbs, of the disturbing attributes of the American Dream. The comfortable nature of the song is a trick really. It holds you and warms you while Win Butler sings of “not believing that they (the children) are moving past the feeling”, the feeling of childhood. The opener ends with waves of strings that evaporates into a single synth note that thrusts into ‘Ready to Start’. Now the fire is burning. The album begins to get a bit more energy, but never breaking out of its shell. That is one of the cool things about this album, everything is completely contained which could easily be a metaphor for the entrapment of suburban life and the uneasiness that one would feel within it. Butler croons on about businessmen drinking his blood, a line that is distinctly powerful, speaking on the idea of an artist having to sell their souls to make art.

After meandering through the neighborhood for three tracks ‘Rococo’ comes in with a different take on the neighbors. The term was stated by the band to mean overdone or baroque music; consequently this song is both – that’s a good thing. A heavy acoustic guitar line forges its way through wispy strings and a harpsichord rhythm while electronic distortion and an accordion slightly alters the thundering song. It adds more and more parts, minimal parts really, until it finally collapses under the weight. ‘Rococo’ lyrically is an anthem, a calling out of faux-educated hipsters; which may explain some of its weight and anger. The song dissolves into ‘Empty Room’ which is reminiscent of Velvet Underground and U2. ‘City with No Children’ speaks of isolation within the suburbs. They focus mainly on the idea of staying in the “private prison”, the only place where they can dream and want to progress beyond the suburbs. “Half Light I and II” finishes the first half of the album, also ending the continuity of the Sunday drive pace.

The second half is a bit more fierce, with the massive drums in “Suburban War”, and punk rock number “Month of May”, which is an anthem dedicated to the frustration they have with the youth of the suburbs and how they spend they’re only time of freedom being pretentious. He screams out to the parent-ally oppressed youth, “I know it ain’t heavy, I know it ain’t light, but how you gonna lift it with your arms folded tight?”. He seems to be speaking from the heart attacking those who choose to limit their already few freedoms because of their musically snobbery. Music seems to be just another weapon of conformity in the suburbs. No one feels it, they only hear it.

“Wasted Hours appears to be the weakest link on the album, just restating everything that “Month of May” proclaimed, and it overstays its welcome with repeated sighs and loops in the verses. Despite that, the new lyrics of children trapped in buses strikes an emotional nerve. “We Used to Wait” begins with a simple staccato piano rhythm that is puts one in the mind of art rockers Spoon, but in the eighties, adding dingy electronics and an offbeat drum part that forces a jittery unease. Butler wails with a different level of passion in this song with lyrics just as uneasy as the instrumentals. The lyrics are filled with the tension of patience and the lack of romanticism and imagination in the youth. The title refers to the idea of writing a letter and waiting for a response. Things like that keeps you on edge alert and always appreciative. The song swirls into a heavy outro with the whole band screaming the title with jazzy back up singing from Regine, who’s unsurprisingly understated and hidden on this album.

“Sprawl I and II” closes out the album with a sorrowful ballad with narrative lyrics that morphs into a power art pop closer. Part one focuses on a group of youth who are being chastised for being out past curfew the song, and the second is the modern man being chastised for questioning his/her reality. The latter track is the first time the Regine takes the lead on vocals, and it is clear why the moment that we hear her sugary voice. She personifies the innocence that is needed in the youth and is only discovered once an adult has looked back longingly at their adolescent years. “The Suburbs (Cont…)” frames the album taking us out in a daze as Win and Regine alternate lead vocals. Its almost like a fleeting notion. This album has floated away just as our “feeling” has. Our creativity, our innocence will remain a nostalgic dream.

Arcade Fire has made a beautiful record that chronicles the thoughts of every adult’s subconscious. It summarizes every feeling, coloring the sentiments of a visionary amongst the masses. The Suburbs length forces you to wait and to take in all in, to slow down for just a moment and dream. That will be consider a flaw to some, and admittedly it kind of is, but it is something that is needed. They gave up a bit of accessibility to make something that they felt, and if one doesn’t nitpick it works. The album,sticks religiously and unswervingly to its theme musically – every chord is uneasy, every tempo is measured. They all in all are making art, and its on there terms. Does this live up to BBC’s praise? I would say so. Its a flawed piece of genius that should be in every music lovers collection, but it should also only be played on occasion so that it keeps its passion.