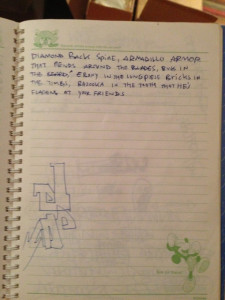

Aesop Rock, early 2000s. (mushrecords.com)

“People can label me whatever they like. I don’t really care any more…I get told that I’m weird—but you forget that the whole reason you liked [Boogie Down Productions] in the first place was because you never heard anything like that before.” – Aesop Rock, quoted in the Harvard Crimson, 2003

As Ian Bavitz was writing the songs that filled out the 70 minutes of Bazooka Tooth, hip-hop was undergoing a protracted identity crisis. When the album dropped, ten years had passed since The Chronic had redefined the way that hip-hop was produced and marketed. Even as the 21st century ushered in an era of exponentially caving-in space-time compression, five years since a pair of game-changing deaths (in addition to the events of Columbine High School, September 11, 2001 and immediate eternity of unfocused war) gave an increasingly corporate hip-hop industry plenty of time to back away from controversy in a cartoonish manner. This is not to say that 2002 was a bad year; Phrenology, Quality, Original Pirate Material and others provided antidotes to the ubiquity of Nelly and Ja Rule. Unfortunately, the canon of chart-topping hip-hop across the end of the century contained an insurmountable number of songs about absolutely nothing.

A few months ago in early mid-2013, Jamie Meline and Mike Render released a collaborative theme album entitled Run the Jewels, a front-runner for many critics’ hip-hop album of the year. The second track opens with a verse by superstar Big Boi.

“If you told me ten years ago that El-P was going to release a single with Big Boi, I would have called you crazy,” said my friend Ted the first time we listened to the song.

In 2003, Company Flow and Outkast were more so marketable ideas than extant groups, but both had been immeasurably influential on drastically different scales over the prior five years. By the turn of the century, Funcrusher Plus had put El-P and subsequently his label Definitive Jux on so many nascent hip-hop fans’ maps, and Stankonia put Big Boi and his erstwhile partner Andre 3000 into bigger houses. But within a few years, Outkast had split into two colorful halves and the brains behind Company Flow had set out on his own and unleashed his own fantastic brand of damage on an overindulged hip-hop world. Neither Facebook nor YouTube would exist for another couple of years, so MTV still had some artistic stranglehold. Hip-hop’s identity crisis played itself out on dying legions of CRT-monitors across the world. While Nelly was busy scanning a credit card in an exploited model’s ass at the end of the “Tip Drill” video, El-P was wandering around New York, getting radioactive guns pulled on him everywhere he went as he rapped “Deep Space 9mm.”

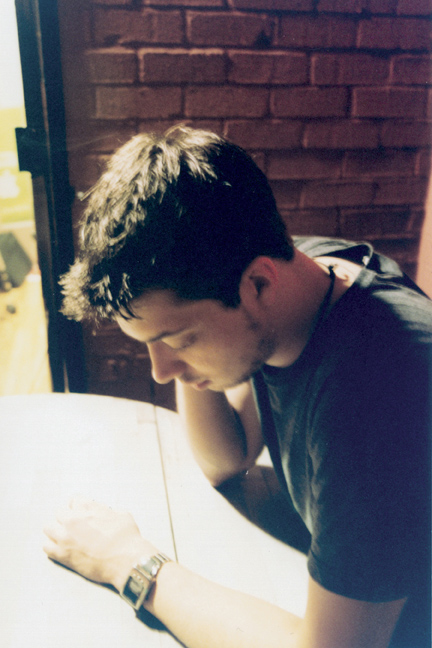

Murs, El-P, Blockhead, Cryptic, and Aesop, early 2000s (yameenmusic.com)

Had Def Jux’s moment in the sun come today, who knows how the lethargic minefield of PBR-financed music blogs and YouTube videos disguised as lazy websites would mishandle the label’s collective message. But by 2003, still well after the Napster-ingrained moment when college kids regularly saw fit to apprehend music by whatever non-monetary means necessary, every release branded with the Def Jux label was feverishly devoured. These included landmark releases by El-P’s friends in Cannibal Ox, the British turntable wizard RJD2 (Deadringer, seriously) and most significantly, an enigmatic, racially ambiguous Long Islander who called himself Aesop. In 2001, Aesop Rock had helped rocket Def Jux from relative obscurity (amongst anyone without their ear to the ground of the East Coast indie hip-hop scene) when he created and dropped Labor Days. Unprepared for the circumstances of this trajectory, he recoiled as his label blew up amongst indie tastemakers and increasingly influential online music filters. On September 23, 2003 he released his auto-iconoclastic follow up, complete with surreal cartoon album art, a nonsensical name, and an unforgettable pastiche of antisocial hip-hop songs splayed across the album’s seventy minutes like a string of tags and slogans spray painted on the side of a rusted-to-death cargo train sitting forgotten on Staten Island.

The most nostalgic cats are the ones who were never part of it. (El-P on “We’re Famous”)

Allow me to begin with the story of how Bazooka Tooth evolved over the course of this past decade into this writer’s favorite hip-hop album of all time. I had missed the Labor Days train two years prior, which still disappoints me, but my introduction to Ian Bavitz later came at a crucial point in both his career and my own life.

As a budding music fan, I was unable to avoid hip-hop. When I was in fifth grade, Snoop and Dre hit my television screen at least once a day. It took me well over fifteen years to realize how important (and legendarily good) “Nuthin’ but a G Thang” had been. Legions of my fellow white kids swallowed the romanticized fantasy world of gats, rims, and bitches, but I rejected it wholeheartedly. I was adequately disillusioned when Tupac died, but his music had never gotten through to me. It simply seemed insincere to me (and still does) that people who never really had to struggle for anything were coddling together sympathy for mass-marketed “thugs” or thugs.

For the majority of middle school and high school, I avoided disappointing my mom by bringing home any CDs defaced with Tipper Gore’s two-tone ego crest. From what I recall, the first pieces of music I bought that carried the Parental Advisory tag were cassettes, The Bloodhound Gang’s One Fierce Beer Coaster (a gem of mid-90’s mookish satire) being among them. I kept dabbling in hip-hop, rap, and techno as the 90’s progressed and got weirder, but it wasn’t until I was firmly lodged in the pseudo-intellectual bubble of the four-year university that the “hip hop as sociology” puzzle began making sense.

Inspired by the buzz around this rapper’s name, I burned a CD-R of my college radio station’s promotional copy of Bazooka Tooth. Within ninety seconds into the opening/title track, Ian Bavitz’s obtuse, obscure lyrical flow and four-pack-a-day rasp had earned a new, enthusiastic fan. Despite the floodgates to content that Napster, Limewire, and the like had opened to me by age 20, I had never heard anything like the clinking and clanking nihilism of that opening track, and it still resonates.

I kept a radio-censored version of the album on steady rotation throughout my junior year of college. I was still accustomed to mainstream, professionally engineered radio edits on hip-hop songs that covered their audible tracks, but these weren’t clean and didn’t seem professionally engineered. They simply highlighted the swear words, twisting and reversing them on an ostensibly limited budget. To this day, I still imagine Skipper labeling dolls with the name of “Yiddish” rap artists prior to “tearing their still-beating hearts out of the loose-leaf carcass.” It took me a couple of years to get my hands on the original version. I was actually disappointed to hear that Aesop had in fact referred to “shitty” rap artists on “NY Electric” rather than slide in this nod to his own ambiguous Judaism (I never knew anyone with his last name and wasn’t the only one of my friends who wondered this; he was actually raised Catholic).

I had no idea that Aesop’s longer-time fans held Bazooka Tooth, with its undeniably muddled production and less-coherent lyrics (than that of his first few releases, at least) in relatively low regard, particularly next to the mind-blowing dexterity on earlier tracks like “Flash Flood” and heart-stopping storytelling of “No Regrets” (I still care deeply about Lucy, whether or not she was based on a real person). I was not the only one who liked this album, yet I was one of the few people I knew who loved this album. I saw nothing wrong with a rapper challenging his listeners with double-talk and mondegreens. Considering the post-internet, pre-social networking era that Aesop’s mid-twenties works existed in, this was not much different from David Lynch challenging his viewers with analeptic plot devices or David Foster Wallace challenging his readers with a novels’ worth of dense footnotes.

Back artwork from release (from Amazon).

In fact, when I continue thinking on this, the Bazooka Tooth triple-LP set was the first record I ever bought new. Until that point, I was a dilettante accumulator of used vinyl for leisure and novelty. After this shiny, beautifully illustrated record broke the ice, I increasingly began taking vinyl more seriously. (Equally noteworthy, if connected more to Aesop than this particular work: When I joined Thefacebook.com in 2004, I listed “Fast Cars, Danger, Fire and Knives” under my interests section. It stayed there for a surprisingly long time).

Anyway, that’s enough self-absorbed nostalgia from me. I included this to illustrate one of several reasons why Bazooka Tooth deserves this level of tribute as it turns ten, especially since I know that my story is hardly unique. This record is a difficult one to explain and (whenever necessary) defend, but there is too much insanity packed into these fifteen tracks to explain under the pretense of linear thinking. Let’s go to the tape.

Hyde heckles Jekyll and makes Hitler look cuddly. (Aesop on “Cook It Up”)

When you are white and male, society opens an extraordinary number of doors for you. This flies in the face of an irreparably shitty post-millennial job market, privatized higher education producing near-lifelong debt, and any memory of when this system you were born into was completely worth the hassle. It’s particularly unfortunate having entered the real world right as any hope of succeeding in your parents’ footsteps faded over the horizon and crumbled behind the World Trade Center, surrounding for years by people who can still smell metal in the air tonight. Regardless of when or how you fail, you get chastised if you blame anybody but your hegemony-feeding white male self. You never had to fight racism, sexism, or (necessarily) classism, so what claim do you have to a struggle?

Bazooka Tooth wasn’t my introduction to twisted, nerdy hip-hop progenitors, but to put it bluntly, it was the first time one of these weirdoes (as C-Rayz Waltz proudly declared his crew on a VHS documentary about their label) blew me away. Aesop Rock led to El-P led to Sage Francis led to me starting to actively disintegrate the prejudices I’d had against hip-hop in a whole new context. While it would be patronizing and unfair to juxtapose the “black struggle” with any type of “white struggle,” Aesop, Sage, and others illustrated that there was such a thing as the latter with increasing proficiency. It just wasn’t externally inflicted. Growing up unable to meet high expectations, being condescended to by peers and adults for being “weird” or “different,” and unable to find a comfortable medium through which to develop, aren’t tantamount to society thinking you’re a problem, a leech, or “not a real American,” but that doesn’t mean one’s life can’t objectively suck. A generation of suburban kids who had grown up thinking (for some reason) that Kurt Cobain Billy Corgan understood their frustration now had a whole new fucked up set of intellectual leaders that were nerdy, wore their damage on their sleeves, and couldn’t care less if they fit into any profession. Even the most highly trained were capable of failing and shooting forty-one shots over par. El-P and his friends decided to build their own scene, and around the time that Bazooka Tooth dropped, kids of all races who loved television and manic depression were listening.

(LAmusicblog.com)

“No bad moves allowed when you are in the public eye; kill it, you are the weakest link, goodbye.” – Aesop on “Easy”

This exposure and ground-level fame came unwelcome to an under-prepared agoraphobic who admitted that, for a stretch of his early twenties, he couldn’t leave his house without getting dizzy and falling over. Ironically, this was exactly the anti-bravado that hip-hop needed to recapture its appeal to those alienated by big booty bitches and cars that creditors had probably already repossessed from Mystikal. To even call this music “street level” would be a misnomer, as its progenitor spent much of his early twenties too much of a jittery, drooling mess to walk down any street, risking exposure to either the cameras or guns, one of which were going to shoot him to death. “Aesop Rock” was already a suitable stage name for a gifted lyricist and uncompromising personality, but now, even his pseudonym needed an alter ego into which he could safely retreat. We all made Bazooka Tooth; we’re all guilty.

Wisely, Bavitz and his cohort gave the obtuse Bazooka Tooth a few years to age before he demystified his back catalog with an official lyric booklet in 2005 with the deluxe release of the Fast Cars, Danger, Fire and Knives EP. Reading along with these songs for the first time (and each subsequent time) brought about dozens of aural epiphanies (I’ve been listening to this record consistently for a decade without noticing the ‘Heavy Metal Parking Lot’ reference). This was particularly true in the case of tracks like “NY Electric” and “Freeze,” where Aesop’s anger over both New York’s compromised life condition and his own fame were palpable, if not completely coherent at first. Provided with the comprehensive lyric sheets, the listener was able to connect these dots, but a tangled jungle of pop-culture references still confronted them. Bavitz’s categorical obsession with comic books of his youth and obscure political scandals lent itself surprisingly well to critically dense poetry that almost transcended his formal (four-year college) education. He had already established himself as one of the most impressive MCs in independent music, but now he had proven himself one of the most confrontational lyricists, too. It came at a time when Hip-hop needed a solid set of middle fingers to flash at convention, and Aesop, Murs, El-P, Mr. Lif, and company were happy to extend them. It still surprises me to remember that Bavitz was only in his mid-twenties when he recorded Bazooka Tooth. At the time, it wasn’t so shocking to college-age kids like me, since 25-year olds had so much life experience that we lacked. The surprise is that even now that my cohort and I have surpassed that cornerstone age and then some, Aesop’s wit and perspective on songs like “Babies with Guns” and “Kill the Messenger” still sound like they come from a mind way more developed than my own.

“Ain’t it strange it’s a fad to bite your idols when the only reason you liked them was cause their shit wasn’t recycled?” – Aesop on “Frijoles”

Charcoal design by Nell Nealy (taltopia.com)

If the blatantly unsolved murders of Biggie and Tupac sent hip-hop into a political regression of sorts, it was equally unsolved, untimely murder of Jam Master Jay that really stepped on the collective throat of Bavitz and his label mates. The violent realities of an out-of-control capitalist venture had already begun setting in by the time that Meline began burning his poetry onto vinyl in the early 90s, but it all paled in comparison to watching a pioneer fall. Run-DMC, as arguably the most influential rap group of all time, was suddenly no more, and as painful as this reality was, the slate had, in many ways, been cleared. On “Freeze” (the closest thing this album had to a single, or hit), Aesop concludes the song with a nod to Jam Master Jay’s “resurrection and second death,” which acknowledged how nobody was forever, even if your heroes’ music lived on eternally. Mizell’s October 2002 murder happened right around the moment before Hip-hop had come of age sufficiently to reflexively capitalize off its own nostalgia. Before long, a new race to the top had begun. As his label hit an arguable peak with this succession of releases by Can Ox, RJ, and Aesop, El-P didn’t waste the opportunity to remind people about where he and his progeny had won any succession of little victories as the hip-hop “industry” allowed over the turn of the century on “We’re Famous,” a very unconventional version of one of hip-hop’s great conventions (the diss track).

Nobody involved in the Def Jux process seemed content resting on any laurels. Countless rappers that Ian and Jamie had grown up watching had worked (and innovated) their asses off until earning that coveted SNL appearance, that insurmountable platinum record, and then simply got lazy. In retrospect, Bazooka Tooth was a logical step in a career for a rapper who never cared to be confined to peoples’ expectations. In the decade since, he has reunited with Blockhead (“None Shall Pass”), united with Kimya Dawson (“Uncluded”) and even, in the single most controversial move of his career, left New York for the Bay Area. The man that once thickly territorialized his domain over the five boroughs might have taken his own advice and shot himself in the foot while it was in his mouth if he honestly gave a shit what people thought. The ostensibly white rapper with a Boston University diploma, dropping Suzanne Vega references during free-styles, had his mind made up. Satisfyingly, he has found ways to grow musicially as well as ways to keep getting weirder; he promoted his latest solo album Skelethon with a web-series that featured him dragging a dead cat around a hallucinatory San Francisco. Is he trying to lovingly deconstruct his new city in the way in which he did New York? Bavitz may not be Jewish, but one could make the argument that he’s successfully evolved into hip-hop’s fucked-up take on Woody Allen.

“Brinker 1-9, 9-11-01 Witness. Maybe you don’t get this.” – Aesop on “NY Electric”

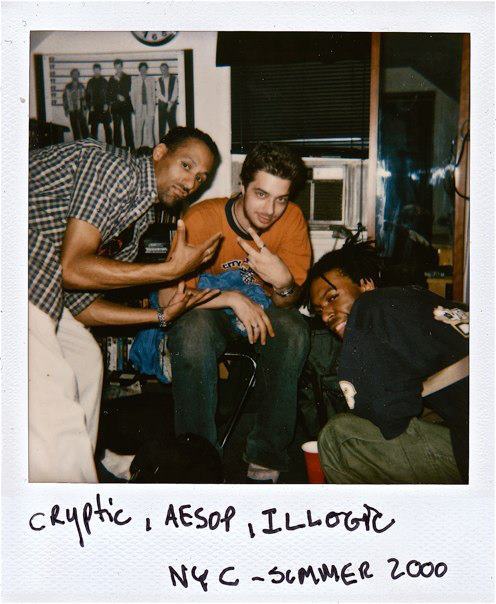

(from Cryptic’s tumblr)

While hip-hop was floating relatively irrespective of the streets, Aesop Rock and his cohort were engineering hostile beats and noises on personal computers in smoke-filled apartments. Whether or not they realized it at the time, they were setting the tone for an exponentially increasing trend in bedroom-production. Additionally, their love of the music they were creating transcended their hatred of their situations, and it showed. Despite Aesop’s professed love of soaking up dialogue from films that ‘take place in other eras and other places,’ the early 2000s had locked him solidly into New York, as if there was anywhere else he could have gone. This once-invincible urban wonderland had folded to this dystopian reality where it was suddenly possible to curfew the city and shut down every block. The Big Apple has yet to regain its glory.

To New Yorkers, especially starving artists, 9/11 wasn’t the end of life as they knew it, but it did exacerbate everything that had already been shitty about their lives. “When you’re a poor person,” confined Vast Aire in the aforementioned documentary, “24 hours is like 10 years… When you’re not poor, time is leaving you. Money is everything, and that’s just sad.”

In 1961, activist and urban studies guru Jane Jacobs wrote that “Time, in cities, is the substitute for self-containment. Time, in cities, is in dispensable.” The poor urban dweller is consistently wondering where their family’s next meal is going to come from; days, hours, and minutes move slowly. Time stretches out like the poly-rhythmic, cumbersome beats on Aesop’s record. Nobody intended to let anyone dance to this joint. Why would anybody want to? On the most arguably dance-able track, “11:35,” Mr. Lif cites a poor immigrant named Jose falling to his death in an industrial grinder, among other modern-day micro-tragedies, before the beat cuts to a jerky, uneven shuffle for no apparent reason. Building upon a series of sentiments (alienation, depression, inertia, paranoia, agoraphobia), Aesop mans the production helm, mixes molasses into the aesthetic, and paints that long-overdue picture of a dystopia-tinged New York, that defeated metropolis where biggest brother’s watching bigger brother watching big brother watch you, spectral particles of the world trade center permeate the atmosphere, and in distinct corners, angry young men dig through neighbors’ garbage and shoot decrepit, sickly dogs behind barns. Fittingly, Vast Aire materializes at the end of “NY Electric” to eulogize the world where buildings fall and hopes crash.

Instead of turning this anxiety inward as he did so often and effectively on Labor Days, Aesop was now projecting these sentiments clearly across the world’s picture-in-picture widescreens and outward onto the human race (itself now an endangered species and willfully hunted by each other, including their infants). The species is ripe for a takeover at the hands of Martians, which is exactly what happens at the end of the album. Conceptually, Aesop’s fantasy of a decisive Mars victory is far-fetched, but hypothetically who could argue in favor of humans after over an hour of unflinching misanthropy?

“Every leader dead and it’s making you upset.” – Aesop on “Kill the Messenger”

There’s no way of knowing where Bazooka Tooth would have gone if Def Jux or Rhymesayers released it today. It would still have acolytes, no doubt, but who would be downloading any of the singles off iTunes or which radio stations outside of New York’s proudest independent and pirate stations would take a risk on any of it? It remains a document of a particularly triumphant era for underground hip-hop as the underground emerged, rubbing its eyes at the strobe lights and adulation. Considering how much has changed in this past decade for both Aesop, El-P, and backpacker hip-hop (if anyone even uses that term anymore), their string of timeless works under the strangest conditions is remarkable, fomenting a style of revolution that will not be apologized for.

To me, Bazooka Tooth is the strongest microcosm of this moment in time, and I know that many people (possibly even Bavitz himself) may disagree. But as the record proved ten years ago, cryptically and consistently, we live in a world with no simple answers, and the answers that seem simple are going to fall out from beneath us when the impending end of days crushes New York along with the world that its residents believe revolves around it. In Meline’s half-joking words to an interviewer a decade ago: “You didn’t realize that we were in the middle of World War III and that we’re all gonna die soon?” Aesop Rock understood that time, his crew’s city, and even the human race were changing too fast to even recognize when he pieced this disturbed anti-masterpiece together. One generally painful decade later, we can still take comfort in how no matter what happens, we’ve got something built if we all die tonight.

“Bazooka Tooth,” baby.