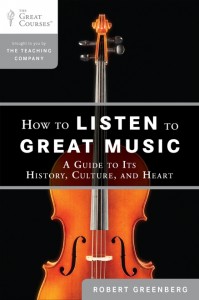

This is a guest post by Robert Greenberg, author of “How to Listen to Great Music: A Guide to Its History, Culture, and Heart”

WE were told as children, “sticks and stones will break your bones but words will never hurt you.”

Wrong.

In truth, words have the power to inflict tremendous hurt: spiritual, emotional, and intellectual. Among the worst offenders are terms of classification: those handy-dandy words and phrases that allow us lump things together irrespective of their details and idiosyncrasies. Innocent though they might appear, such terms can enchain those things they classify forever, locking them in place, never to be reconsidered again.

Under such circumstances, words can make us stupid. Stupidity is hurtful. Words, my friends, can hurt us.

“Classical” Schmassical

Among the stupidest phrases ever created is “Classical music”, a phrase as meaningful as “compassionate national socialism.” The term “classical music” is broadly understood to apply to a body of music composed by dead Euro-males between roughly 1650 and 1900, music usually heard in the environs of a concert hall or opera house. Speaking correctly, when we call something “classic”, we are identifying it with the exquisite clarity, proportional balance, and emotional restraint of ancient Greek art. This definition immediately rules out the great bulk of the music we would call “classical”, music that in reality is often filled with more angst, storm, and stress than a trip to the proctologist. Even if we use the word “classic” in its loosest form — to indicate something exemplary — who’s to say that the phrase “classical music” shouldn’t apply equally to “Classic Jazz”, “Classic Rock” — and yes, even “Classic Disco”.

I would humbly suggest the phrase “classical music” be tied to a rock and thrown into the Marianas Trench, to be replaced with the term “concert music.” Admittedly, not all “concert music” is performed in a concert hall (performances often occur in churches, school auditoriums, living-rooms, and so forth); admittedly, jazz and rock — which by our definition are not “concert musics” — are often performed in concert halls. Nevertheless, the phrase “concert music” — its flaws aside — is a thousand times less subjective and therefore less offensive than “classical music”.

Who put the “pop” in “popular”?

The phrase “Popular music” is used to identify music that presumably grows from the soil of popular culture rather than from the artistic impulse of a singular creator. Used its broadest sense, “popular music” is applied to such a wide range of music as to be, in truth, useless.

Many academes prefer to use the phrases “cultivated” and “vernacular” to describe, respectively, concert music and everything else. Like “classical” and “popular”, classifying music as being either “cultivated” or “vernacular” creates a false dichotomy while, at the same time, tossing in a lumpy dollop of subjectivity as well. I mean, who wouldn’t rather her work be considered “cultivated” (with all the elegant conceit that word conjures up) than “vernacular” (meaning of the “common tongue”)?

Show us the MONEY

Other folks would tell us — with a straight face, even — that the difference between “popular music” and “concert music” has to do with its commercial intent: that popular music is written for money and that concert music is created for the sake art, far removed from the tawdry monetary environs of the marketplace.

Please. Anyone who believes that Haydn or Mozart or Beethoven or Verdi or Wagner or Brahms or any of those cats composed merely for the sake of their “art” is living in a fool’s paradise. They were professional composers. Professional composers write music for a living. Living is expensive and composers compose for money.

The Write Way

So, how are we to distinguish between “concert music” and jazz, rock, folk, Zydeco, etc. in such a way that non-subjectively draws its relevance from the substance of the music itself? I would suggest the following.

The overwhelming bulk of concert music is composed music: music that has been fully notated, that is, entirely written out. Concert music, because it is so scripted, is an interpretive art. It is also an exclusive art: the occasional embellishment aside, it excludes those pitches and rhythms not notated by the composer. To perform otherwise is perceived as having made a mistake.

Let’s Talk About It

The overwhelming bulk of jazz, rock ‘n’ roll, folk (and so forth) is conversational music: music that grows from the oral tradition and is not fully notated. Instead, frameworks are created — chord progressions, rhythmic sequences, and formal structures — within which performers are expected fill in the blanks depending upon the inspiration of the moment, from simple thematic embellishment to outright improvisation. As such, a jazz or rock or folk performance does not just interpret the piece under performance, but actually recreates that piece anew every time it is performed.

Now, I will be the first to admit that the terms “composed music” and “conversational music” are as plain as a mayo on Wonder bread sandwich. Nevertheless, they have the advantage of describing the actual substance of the music they purport to identify without rendering — implicitly or explicitly — any sort of value judgment; they identify without hurt. For that reason alone I would suggest we consider using them or, at very least, think about them.

Author Bio

Robert Greenberg, author of How to Listen to Great Music: A Guide to Its History, Culture, and Heart, is a speaker, pianist, and music historian. He has served on the faculties of UC Berkeley, California State University East Bay, and the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, where he was chairman of the Department of Music History and Literature and director of the Adult Extension Division. He is currently music historian-in-residence with San Francisco Performances and also serves as the resident composer and music historian to NPR’s Weekend All Things Considered. Since 1993, he has recorded over 550 lectures for The Great Courses.

Robert Greenberg, author of How to Listen to Great Music: A Guide to Its History, Culture, and Heart, is a speaker, pianist, and music historian. He has served on the faculties of UC Berkeley, California State University East Bay, and the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, where he was chairman of the Department of Music History and Literature and director of the Adult Extension Division. He is currently music historian-in-residence with San Francisco Performances and also serves as the resident composer and music historian to NPR’s Weekend All Things Considered. Since 1993, he has recorded over 550 lectures for The Great Courses.

Founded in 1990, The Great Courses produces DVD and audio recordings of courses by top university professors in the country, which are sold through direct marketing. It is a nine-figure-a-year business and they distribute forty-eight million catalogs annually. They offer more than four hundred courses on topics including business and economics; fine arts and music; ancient, medieval, and modern history; literature and English language; philosophy and intellectual history; religion; social sciences; and science and mathematics.

For more information please visit http://www.